When I was little, I wanted to be a detective. Or a writer. Or a writer of detective stories. Indecisive from an early age, I was not quite sure which appealed most – or maybe it should be a combination?

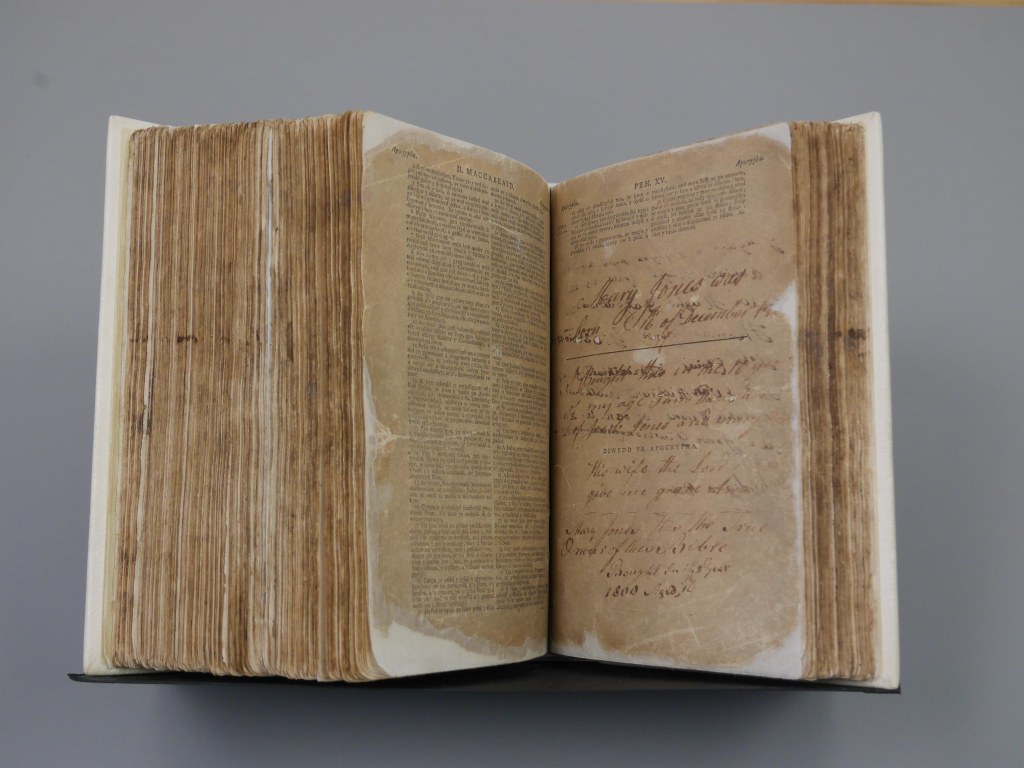

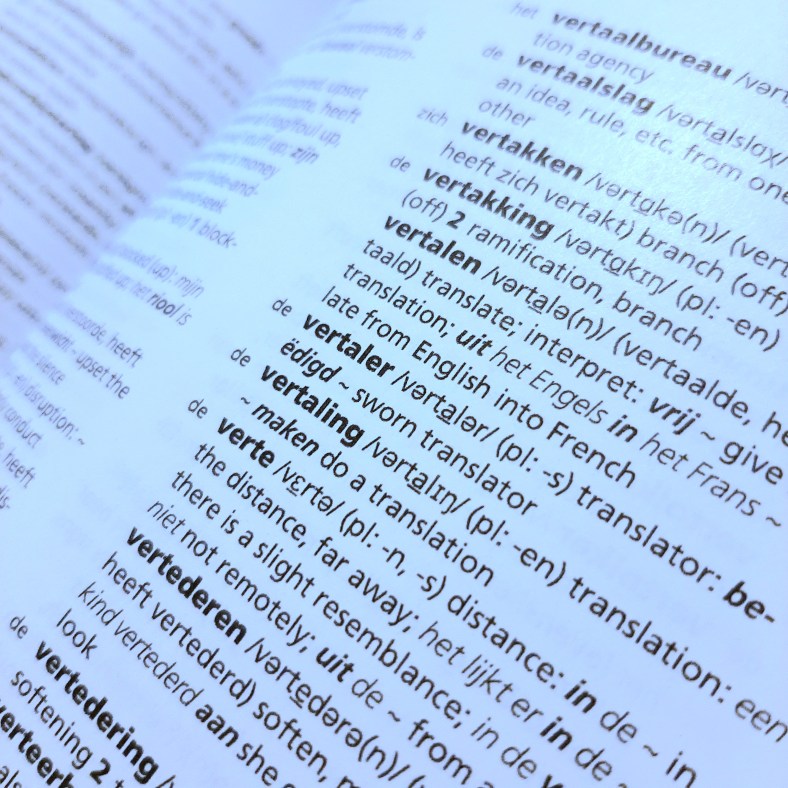

In any event, I was very clear about the kit required. I had notebooks (always lots of notebooks!) for both professions. For detection, I also had a magnifying glass (of course – I was an early acolyte of Sherlock Holmes) and a toy revolver (no doubt influenced by reading too much Raymond Chandler at too young an age). I had a range of disguises, including spectacles, moustaches, and greasepaint. I improvised a fingerprint set with sellotape and ground-up pencil graphite (with surprisingly clear results). For writing, I had the Pocket Oxford Dictionary (single volume – a navy blue hardback way too chunky for anyone’s pocket), a selection of pens and pencils, and a modest library of books for inspiration. I aspired to using a typewriter, because I knew that proper writers always typed their manuscripts, but my fingers were not yet strong enough to strike the keys of my father’s Remington Envoy.

Quite where these tropes came from, I’m really not sure. I watched very little television (for most of my childhood we didn’t have one), and I was home-educated so there was not much in the way of popular culture influences. There was, however, the BBC World Service, which was then a much more holistic broadcaster than its present incarnation as a rolling news station, and was responsible for much of my classical and jazz musical education as well as introducing me to Shakespeare (a production of Twelfth Night), Tolkein (The Hobbit, read by Bernard Cribbins), Douglas Adams (the original radio script, unsurpassed by subsequent books, films and television adaptations, of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy), and Dorothy L Sayers (courtesy of the peerless Ian Carmichael as Lord Peter Wimsey – when I subsequently read my grandmother’s copies of the books, it was Carmichael’s voice I heard). The World Service also broadcast the sit-com The Small Intricate Life of Gerald C Potter, where the eponymous detective writer (again played by Ian Carmichael) and his wife Diana (a much more successful writer, creating breathless romances under the pseudonym of Magnolia Badminton) crashed amusingly through a more or less chaotic but never boring life, accompanied by the sound of a manual typewriter. It did nothing to lessen the appeal of wordsmithing as a lifestyle. The signature tune, Leroy Anderson’s The Typewriter, still makes me smile.

There was no shortage of role models for my future career as a detective. My grandmother had a serious addiction to Golden Age crime fiction (in the original English, despite being an elderly Dutch lady) and I was exposed to Hercule Poirot, Jane Marple, Parker Pyne, Lord Peter Wimsey, Perry Mason, Philip Marlowe, and of course Sherlock Holmes, even before I graduated from reading Enid Blyton’s Secret Seven and The Five Find-Outers.

I have always believed that names are important. Naturally, my detective alter ego needed a name, and for some reason which I have long since forgotten, I decided on Peggy Reynolds, Private Investigator. As a nascent writer, my nom de plume was Mara McDonald, and I do know the origin of that – it was the result of a brief infatuation with all things Highland caused by overdosing on Robert Louis Stevenson and reading Kidnapped under the bedclothes with a torch. I was more than a little in love with Alan Breck Stewart, self-aggrandising and infuriating as he was. Looking back, it is interesting to see the association in my young mind between writing and romance.

Fast-forward nearly half a century. What would that child, who responded to the tedious adult questioning about ‘what do you want to be when you grow up’ with such interesting ambitions, think of how life has turned out? Well, I never did become a PI. However, my insatiable curiosity, my obsession with collecting obscure facts, and the desire to find out how things work have stood me in good stead in a variety of jobs. Detective instincts are especially useful for the writer of non-fiction, who inevitably needs to invest large amounts of research in every piece of writing – research is to writing what the base of the iceberg is to the visible tip. And I am, indeed, a writer – even if not currently a full-time one – with a respectable clutch of publications in print and online (the latter something my young self could not have imagined), in non-fiction and poetry. However, fiction has proved to be a genre I simply cannot write, and the dream of writing a detective novel remains just that – a dream.